Not Quite Ready for the Scrap Bin

Marilyn developed macular degeneration sometime around 2015. I can’t pinpoint that date for sure because her eyesight didn’t change much as far as I could tell. Long after her initial diagnosis, she continued to drive back and forth from the grocery store, solve Wheel of Fortune puzzles on TV and cook breakfast, lunch and dinner for her husband Paul.

Macular degeneration and grief

Yet much like the way the swollen creekwater would inevitably extend its muddy reach into her basement after heavy rains, her macular degeneration advanced at a slow, but relentless pace. Adding insult to injury, around the same time Marilyn’s disease took hold of her eyes in earnest, a rapid series of devastating blows struck her heart. Within the space of nine months, one by one, she lost her daughter, her husband, her home and her independence. Marliyn’s outlook and initiative blurred to a grief-heavy crawl.

But there was one thing she tried to keep running: her sewing machine. Purchased back in the 1980’s, her Pfaff 1475CD has cranked out an impressive number of stitches. With it, she’s sewn everything from napkins to curtains to a stunning dress. A wedding dress, in fact, that she happened to make for me. It required an inordinate amount of thread, mostly because she stitched together that Vogue 1060 pattern not once, but twice; insisting on a practice run with muslim before cutting into the expensive silk and lace. I always thought that story said a lot about Marilyn.

From seamstress to quilter

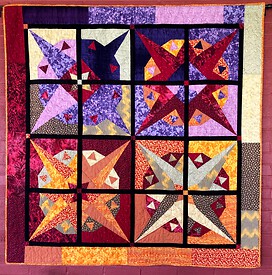

When she was in her 60’s, Marilyn pivoted and took a just-for-fun quilting class. Before long she shifted from seamstress to quilter. Marilyn’s sewing room, a sun-filled space lovingly retrofitted by her husband decades ago and stocked full of patterns, notions and threads, quickly evolved into a colorful cotton-filled haven for calicos, cutters, and of course, scraps. If you know anything about quilting, you know that the scrap pile can take on a life of its own. Bins and tubs and shelves quickly overflow with fabric snippets in every imaginable size, shape and color.

Keeping a few meaningful possessions

Not long ago, while firmly rooted in that aforementioned season of grief, Marilyn was encouraged to move in with her oldest daughter. Space constraints necessitated that she keeps only a few meaningful possessions. She brought along her sewing machine and a small collection of her scraps; a tiny portion of what was once a room-filled inventory of fabric, tools and machinery. Granted, she wasn’t able to keep a lot, but it was enough to keep her busy. I don’t know if it was due to her failing eyesight, her hurting heart, or the stress that comes from being displaced, but sadly, her machine went silent and the dust settled over it all.

A partnership proposition

When people we love are in pain, I think most of us try to do what we can to make them feel better. It comes as no surprise, then, that during one of my out-of-state, post-Covid-vaccine visits, I presented Marilyn with a proposition. A partnership of sorts. One that I hoped would renew her sense of purpose and rekindle some of her joy. As it turns out, I am part of a club that donates homemade quilts to people in need. It pains me to say this, but I am hands down the least productive member of the group. I thought that with Marilyn’s sewing know-how and her dusty bin of scraps, together we might be able to construct a quilt or two to donate. I would enjoy renewed standing in my sewing circle and she would have a reason to get that sewing machine whizzing again. A win-win I envisioned, and just the thing to keep the doldrums of grief at bay.

Marilyn still finds a way

It worked. But make no mistake, it wasn’t easy. With macular degeneration, Marilyn no longer matches points or experiments with intricate patterns. As an accomplished quilt-maker, this is incredibly frustrating to her. But call it a miracle or muscle memory, she still finds a way to thread a needle, change the bobbin and sew straight lines on her machine, creating row after row of strips and squares. Consequently, we have settled into a predictable back-and-forth. During my visits, I cut out fabric shapes from her scraps. (A stash, I’ll have you know, that doesn’t seem to be shrinking in the least.) After I leave, she sews them together and mails them back to me. I assemble these pieces into a quilt top. Once finished with backing and batting, each quilt is labeled and added to the donation pile.

Hope-filled pieces of potential

Today, her routine can still be a struggle. Multi-colored containers stacked in the fridge present daily left-over mysteries. Pills slip through her hands, forever lost in the shadows under the kitchen table. Large-print books are now readable only under a strong light and the perfect tilt of the head. And her heart, of course, is still broken. Yet amazingly, in roughly the same time period marking Marilyn’s back-to-back series of heartbreaks, she has helped me create over fifteen quilts. All assembled in love and paid forward to someone neither of us will ever meet. Each of those scraps, it seems, represents a hope-filled piece of potential; for both the receiver and the giver.

Despite it all, she expands and grows

To be honest, an important footnote to this story is that Marilyn is more than my partner. She is my grandmother. My Scrappy Granny. The nickname originated in reference to her bottomless bins of scraps, but it has stuck for a different reason altogether. My grandmother’s macular degeneration was the start of a difficult season made even more tragic thanks to a below-the-belt series of personal losses. But at 93-years-old, private and quiet, she has managed to squint in just the right way to allow a little light to get through. Even as her physical world becomes limited, blurred and small, she creates and expands and grows. She’s scrappy that way.

When left in a dusty bin, scraps aren’t good for much. But brought out into the open, they sure hold a world of possibilities; creating intersections of beauty from both the suffering and the sacred. Stitched together, mismatched points and all, into this scrappy masterpiece we call life.

Join the conversation